The University of California began to require its faculty members to sign a loyalty oath, and Tolman led a group of faculty members who would rather resign than sign it. They saw the requirement as an infringement of their civil liberties and academic freedom. Tolman was suspended from his duties at California and taught for awhile at the University of Chicago and Harvard University. Finally, the courts agreed with Tolman, and he was reinstated at the University of California. In 1959, upon his retirement and shortly before his death, the regents of the university symbolically admitted that Tolman's position had been morally correct by awarding him an honorary doctorate. (Hergenhahn, An Introduction to the History of Psychology, 1992, p. 374)

In 1949, toward the end of the McCarthy era, the university tried to impose loyalty oaths on the faculty, in conformity to state law. During the "Year of the Oath", 1949-1950, it was Tolman who became the leader of the faculty in the fight against the oath. He refused to sign it but, in his usual style, he made the point that he could afford the financial sacrifice if they were to fire him. He advised his younger colleagues to sign, and leave that battle up to others who were in a better position to conduct it. These courageous efforts brought Tolman widespread acclaim. He received honorary degrees at major universities and, when he died on November 19, 1959, the Washington Post wrote in an editorial: "His death last week is a loss to the nation as well as to the academic community." (Gleitman in Portraits of Pioneers in Psychology, 1991, p. 239)

He wanted us to stand on our own feet and be our own men, not his. Any slavish adherence to his views would have been repugnant to him. So all of us who were fortunate enough to have been associated with him have struck out for ourselves and hopefully we are better psychologists, and yet more hopefully, better people for having been associated with him. (reminiscence quoted in Krantz and Wiggins, 1973)

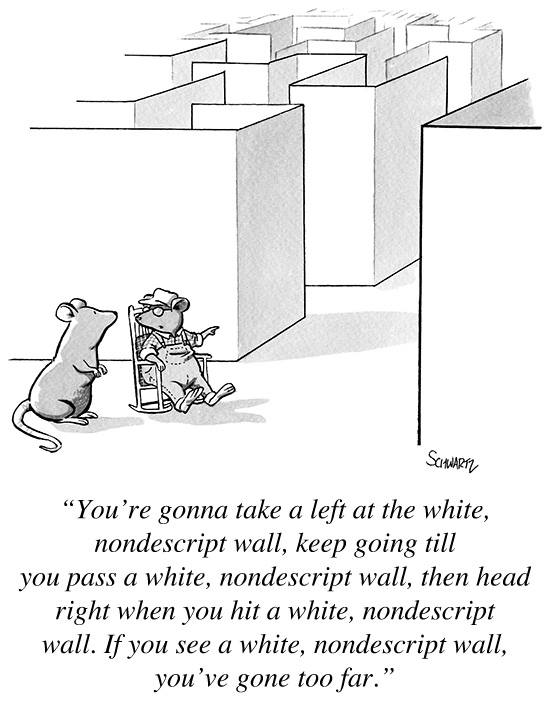

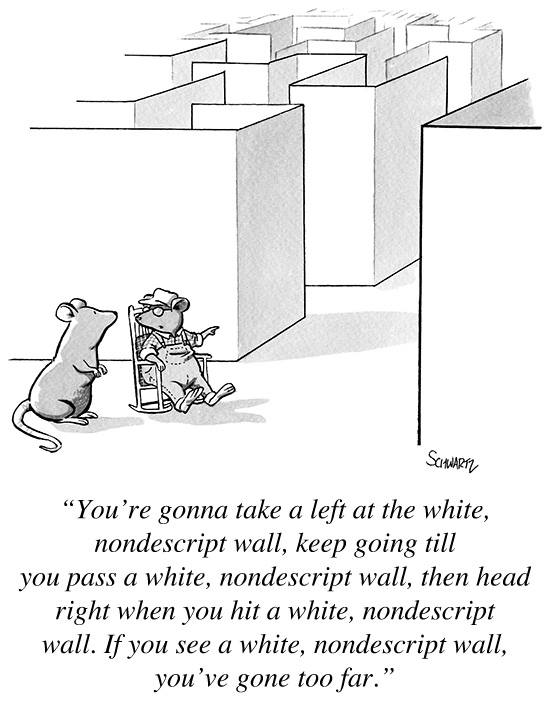

Race a rat through this maze. I'm not saying it's hard, just that he's faster than you think - and the rat doesn't get the bird's eye view that you get either.